The term ‘hippy’ (or ‘hippie’) was controversial: Exclusive interview with Sharif Gemie

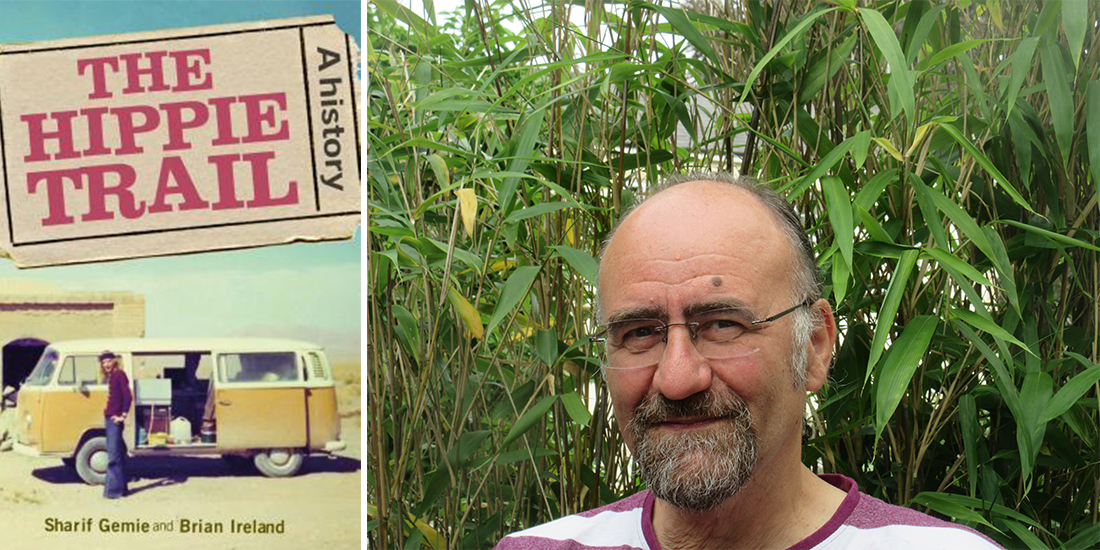

Sharif Gemie is a retired historian who, while working in his field, wrote eight books, among which his most successful one was The Hippie Trail. After his retirement, he turned to writing fiction, and his first novel, The Displaced, about a middle-class English couple who volunteer to help refugees at the end of the Second World War, will be published in April 2023. Birat Anupam has conducted an exclusive interview with Sharif, in which they discuss his book The Hippie Trail, which also talks about Nepal as a hippie destination. Excerpts:

You have written an exclusive book on hippies. You have cleverly used the term ‘hippie trail-er,’ instead of ‘hippie.’ Why did you choose this name?

The term ‘hippy’ (or ‘hippie’) was controversial. It was briefly popular in 1967-68, but after that was frequently rejected. We asked our interviewees about this, and what term they would have called themselves back in the 1960s and 70s. The counter-cultural rebels felt the word ‘hippy’ was artificial and manufactured; the more conformist felt the word ‘hippy’ was too rebellious. ‘Traveller’ was a more acceptable and more neutral term for all of them. We used ‘hippy trail-er’ just for the sake of variety.

This is a research-based book, you have talked to 80 folks, 55 men and 24 women, from the UK, USA, Germany, and the like. You have not interviewed a single Asian guy. Were Asian not hippie trailers?

I’ve got to correct you: I know it’s confusing. We interviewed, face-to-face 34 travellers. We communicated via email and questionnaires with another 11. And we found 35 other works (published books, self-published books, entries on web-sites) relevant to the trail. In total, 80 narratives of travel along the trail (see p. 2 of the book).

Your question about Asian travellers is really interesting. The hippy trail-ers all felt they were travelling to a very foreign land. They often had friendly contacts with Asian people, and they could share with local people their interests in spirituality, drug-taking and relaxed approaches to travel. However, no Asian person would have felt that strong sense that Asia was foreign or strange, therefore no Asian was travelling the hippy trail.

There probably were Asian hippies (or something pretty close), but there couldn’t have been Asian hippy trail-ers.

You have segmented your book into five sections. You have put your opinions at the beginning and the end. How exciting was the whole process of writing this book and reaching out to the whole world?

It was very exciting. The main challenge was that outlined on p. 2: how do you write a history of a movement which was so unofficial and informal, and yet which clearly existed? It was also really interesting to be the first people writing a history of the topic. Others had written memoirs of individual journeys and one or two had attempted sketches which looked a bit wider, but our book was (and still is!) the only history of the hippy trail.

We thought long and hard about the five-part structure. It’s not perfect, it is a compromise between us and the material, but it’s the best we could do.

Many folks link hippie with drugs. However, your finding says their volume was just 25 percent. Why the difference?

Again, apologies, but I have to correct you. On p. 4 of our book we present an approximate estimate of motivations, not practices. About half of our sample did not have any clear motive for travelling the trail, other than a vague sense of adventure or a quest for something exotic. (This is not unusual: we looked at research concerning pilgrimages, and there was the same tendency. Maybe the reasons for the journey were too complicated? Too abstract? Too personal?) Among the other half there were two main motives: i) a spiritual quest and ii) an interest in drug-taking.

Many of the travellers—probably more than half—would have smoked cannabis and tried other drugs. But only approximately one quarter gave this as a reason for travelling east.

Hippie trailers were connectors for some and dividers for other. How did hippe era of 1960 and 1970s shape the contemporary world, especially in the interaction between East and West?

A big question! There were probably two main results. Firstly, the hippie trail was an important chapter in the history of travel, in between the arduous, lonely and imperialist journeys of the Victorian explorers and the easy holidays of the era of mass tourism (now being curtailed by Covid). The hippy trail-ers’ journeys opened up the world: they contributed to a sense that people in the UK, France, India and Nepal could share something. In other words, a sense of belonging to One World. They also provided a different model for travel, distinct from the explorers’ imperialism and the tourists’ commercialism.

Secondly, and more specifically, the hippy trail was an expression of a Western interest in Eastern religions. Buddhism was usually the practice that caught the most attention, and western Buddhism developed institutional bases during this epoch. But other practices and beliefs were also noted and explored (yoga, Sufism and meditation).

You have mistakenly said Buddha was born in northern India. The fact is that Buddha was born in Nepal’s southern plain, in the Kapilvastu district of Lumbini Province. You have not mentioned much about Nepal but have included some hippie trailers’ feedback that Nepal was Shangrila and Kathmandu was Shambala. How was the reaction of hippie trailers about Nepal when you were talking with them for the book?

Kathmandu was often seen as the ultimate destination: along with Tibet, it was probably the strangest and most exotic place that the travellers could imagine. However, many never reached Nepal: they only reached as far as Afghanistan or India. There was a permanent settlement of hippy trail-ers in Kathmandu in the 1960s and 1970s, and the place was celebrated in a song by Cat Stevens. This is one of the few musical evocations of the hippie trail

Those who stayed in Kathmandu often remember it as centre of spirituality.

Your book is co-authored with Brian Ireland and was published from the prestigious Manchester University press. How tough or easy did you feel to write this way?

Brian and I had known each other for about 10 years before we wrote this book. While our approaches to writing and our research interests were different, we found we complemented each other. I can honestly say we had no significant disagreements about writing the work, and much positive stimulus from each other.

MUP were helpful and open-minded. They were willing to accept a book on a theme which was not an orthodox academic topic, and they invited us to select the 22 photos featured in the book.

It’s standard practice for an academic press to find a ‘reader’ who supplies anonymous feedback and suggestions. This process was not difficult or confrontational, but sometimes it was fiddly and complex. I’m still not sure that we properly integrated the sections of academic analysis and the sections directly commenting on the travellers’ experiences: but probably it would be impossible to do this perfectly.