The inevitability of lockdowns in the fight against Covid

Get ready for more

NepalPress

NepalPress

What you can’t cure, one must endure. Covid is precisely that malady. A year after the lockdown imposed in the Chinese city of Wuhan shocked the world, the tactic is turning out to be an enduring tool for quelling the coronavirus almost everywhere. With newer, highly infective strains being reported worldwide, the sceptre of lockdowns still looms large.

When the first large-scale lockdown in modern times was implemented in China on Jan. 23 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was then deemed unproven and unthinkable, particularly by democratic governments who balked at the implications for human rights violations of limiting citizens’ freedom of movement on such a huge scale.

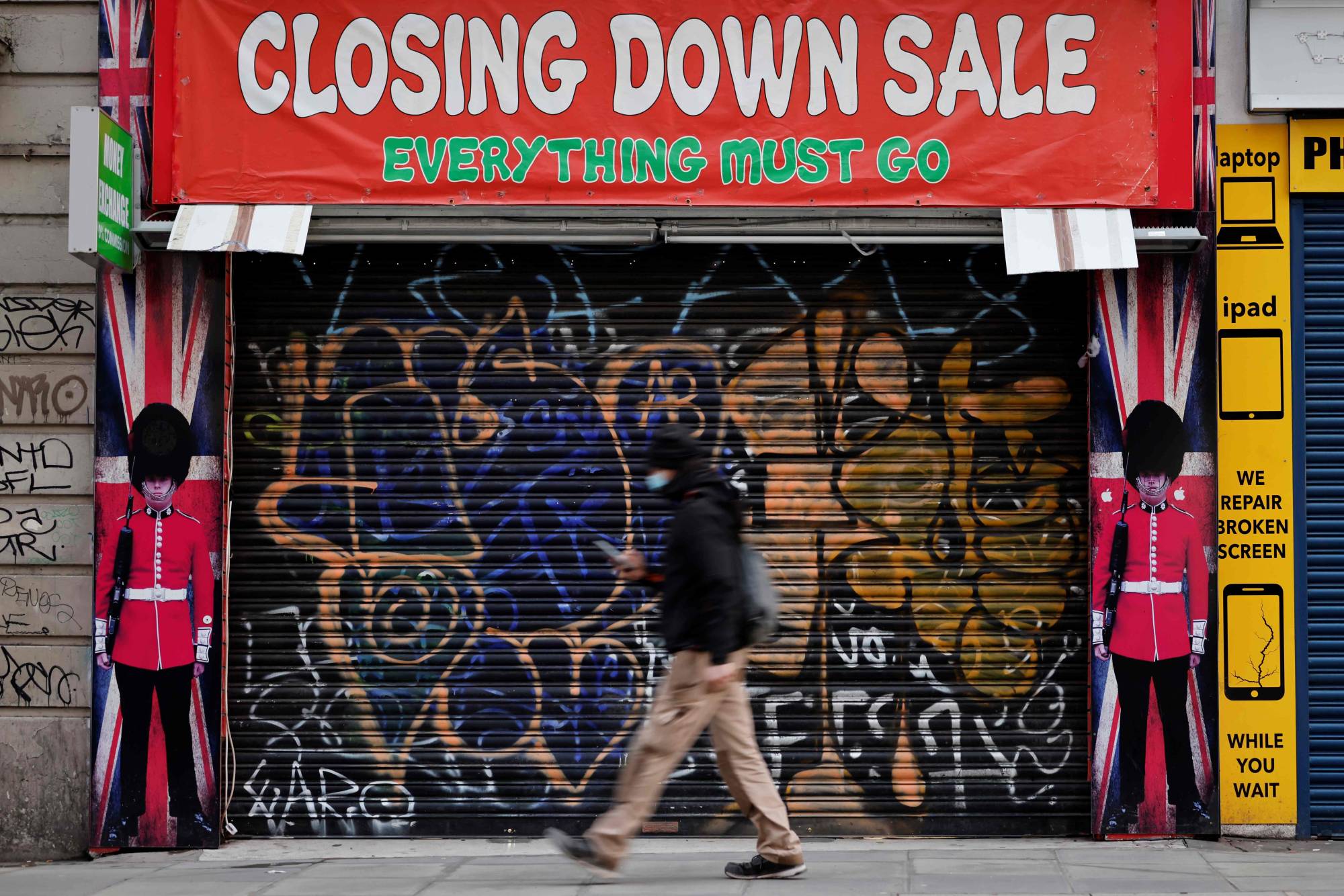

Yet almost 12 months on, the U.K. is in the midst of its third nationwide lockdown as it battles a mutated strain of the coronavirus. In Australia, the recent discovery of one case in Brisbane prompted a three-day lockdown. And China, which is experiencing its biggest outbreak since the start of the pandemic with over 500 cases, locked down three cities surrounding Beijing this month.

“Prior to COVID-19 there was a strong global health discourse that argued against lockdowns and similar mass quarantines. This is but one area of thinking that the current pandemic has overturned,” said Nicholas Thomas, an associate professor in health security at the City University of Hong Kong.

“As far as is possible, lockdowns are going to become part of the essential toolkit for governments to use in addressing the ongoing as well as future outbreaks,” he said.

Wartime measures

The speed with which China locked down millions of people when the pandemic broke out marked the first time that the measure had been taken on such a massive scale in modern times.

Until last year, severe lockdowns were synonymous with the waves of bubonic plague that swept through Europe from the 14th century. Even during the Spanish flu of the early 20th century, no lockdowns were centrally imposed. China did, however, impose three major lockdowns in recent history: during a bubonic plague outbreak in its northeast in 1901, and two short ones following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and another amid a bubonic plague outbreak in Gansu province in 2014.

Foreign countries who were taken aback at the Wuhan lockdown found themselves doing much the same just months later as the virus spread uncontrollably.

After an infectious disease reaches a certain number of people, lockdowns can’t be avoided because no other measure can stem spread, said Jiang Qingwu, a professor of epidemiology at Shanghai’s Fudan University.

It is clear, however, that there remains a large gulf between what the Chinese government is able to impose on its citizens during a lockdown compared with democratic countries. Ever quick to declare what the government routinely refers to as “wartime” measures in response to relatively low numbers of infections, local authorities also ensured compliance by actions such as totally sealing off residential compounds. In some cases, people are not allowed to leave to get food, with deliveries arranged to them instead.

According to the authors of a study conducted by Bloomberg Economics comparing how democratic countries fared against more authoritarian ones in dealing with the pandemic, “a rapid and stringent lockdown is the kind of knee-jerk reaction that comes more naturally to authoritarian than democratic regimes.”

In China’s latest lockdown in Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei province, the stringent measures are reminiscent of those from the Wuhan lockdown, which ended on April 8 after infections dwindled to zero. Residents in the northeastern city, 180 miles (290 kilometers) southwest of Beijing, are required to stay home for seven days as the city embarks on a second round of mass testing for the entire population of 11 million as cases in the region exceed 500. Flights and trains into and out of the city have been halted, as well as almost all public transport.

In contrast, democracies such as the U.K., in their versions of lockdowns, have generally allowed people to leave the house to purchase essentials such as food and medicine, walk their dogs or exercise. Schools remained open in France’s autumn lockdown, while in its latest two-week lockdown this month, Israel is allowing people to gather outdoors in groups of up to 10, with exemptions for religious activities.

But there have also been examples of democratic governments imposing extreme rules. One state government in Australia, where officials have reacted fiercely to flare-ups, banned even outdoor exercise and dog-walking during a brief lockdown in November.

Winter resurgence

Chinese authorities argue that the country’s bounce-back from the crisis proves that their approach works. And a winter resurgence of the virus in countries like South Korea, Japan and Sweden, which originally saw success with a minimal-disruption approach that avoided lockdowns, buttresses the argument for stricter measures, particularly as fatigued citizens flout stay-at-home advice.

“Given the huge number and high density of China, we have proved that (these measures) are very effective,” said Mi Feng, a spokesperson at the country’s National Health Commission.

In addition to concerns over civil liberties, many governments remain hesitant to impose the sorts of full lockdowns as seen in China because of the economic cost — though research by the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook showed that if countries were decisive in taking such measures, they performed better in terms of protecting the economy. New Zealand is one such example, recording just 25 deaths after quickly imposing lockdowns, with life resuming to near normality soon after.

However, even China, whose economy has roared back to life, is cognizant of economic pressure. Since the Wuhan lockdown, authorities have tellingly steered clear of shutting down economically significant cities like Beijing despite substantial flareups. Officials turned largely to aggressive contact-tracing during an outbreak in the capital last summer.

“Effective as lockdowns are, they are costly,” said Yanzhong Huang, Director of the Center for Global Health Studies at New Jersey’s Seton Hall University. “Even for China, it’s unsustainable in the long term,” he added, likening reflexive lockdown decisions to “shooting cannonballs at mosquitoes.”

With vaccinations drives now being rapidly rolled out across major western countries and China, the hope is that lockdowns will be far less common in 2021, though substantial uncertainty remains over how long it’ll take to vaccinate enough of the world population to safely re-open the global economy.

Despite the economic implications, COVID-19’s legacy is likely that lockdowns will continue to be deployed during outbreaks of highly communicable diseases in the future, especially since they’re now a familiar concept to people everywhere for the first time in a century.

“Restrictive quarantine itself is not a new invention and its application dates back to the Black Death in the medieval times,” said Huang. “But it’s ironic that such an old method remains the most effective despite the tremendous progress in medical sciences.”